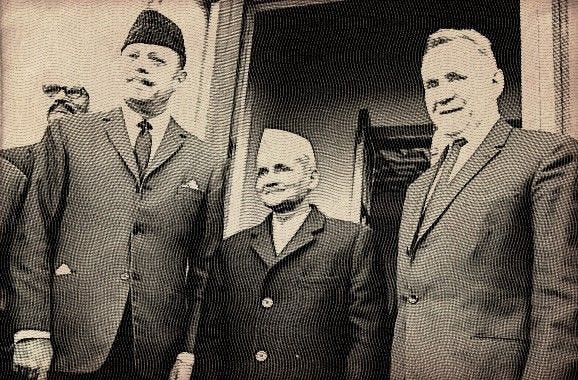

The Betrayal of Tashkent in 1965

Lal Bahadur Shastri died under very unusual circumstances in Tashkent and the reason why he was there in the first place are nothing short of shocking!! In the 1965 War against Pakistan, after India had won the Haji Pir and Tithwa – two important peaks, and made considerable gains, India went to ceasefire talks.

The Betrayal of Tashkent in 1965 #IndoPakWar #Shastri Click To Tweet

Although the war was called a “stalemate” at that time by some and each side claimed victory, but according to many analysts, India held greater advantage and could have made Pakistan surrender within a week.

The war was militarily inconclusive; each side held prisoners and some territory belonging to the other. Losses were relatively heavy–on the Pakistani side, twenty aircraft, 200 tanks, and 3,800 troops. Pakistan’s army had been able to withstand Indian pressure, but a continuation of the fighting would only have led to further losses and ultimate defeat for Pakistan. Most Pakistanis, schooled in the belief of their own martial prowess, refused to accept the possibility of their country’s military defeat by “Hindu India” and were, instead, quick to blame their failure to attain their military aims on what they considered to be the ineptitude of Ayub Khan and his government (United States Library of Congress Country Studies)India held 690 Mi2 of Pakistan territory while Pakistan held 250 Mi2 of Indian territory in Kashmir and Rajasthan, Pakistan had lost almost half its armour temporarily…….Severely mauled by the larger Indian armed forces, Pakistan could continue the fight only by teaming up with Red China and turning its back on the U.N’. (TIME Magazine) [3]

In three weeks the second IndoPak War ended in what appeared to be a draw when the embargo placed by Washington on U.S. ammunition and replacements for both armies forced cessation of conflict before either side won a clear victory. India, however, was in a position to inflict grave damage to, if not capture, Pakistan’s capital of the Punjab when the cease-fire was called, and controlled Kashmir’s strategic Uri-Poonch bulge, much to Ayub’s chagrin. (Stanley Wolpert)

Despite this, when Indian PM asked Army chief General J N Chaudhury, the General either misled the PM or was caught sleeping with no real idea of India’s position of strength! He told the PM that most of India’s frontline ammunition had been used up and the Indian Army had suffered considerable tank losses. While the truth was that only 14% of India’s frontline ammunition had been used, while Pakistan’s 80% had been fired. Despite the fact that Pakistan entered with a superior tank strength going into the war, India (at the time of ceasefire had twice as many tanks still left). [Going into the war, Pakistan had 2 armoured divisions with as many as 675 Patton tanks, including others].

It was with THIS “intelligence” that Indian PM negotiated with Pakistan’s Ayub Khan in Tashkent.

Interestingly, in retrospect, it seems that the Army Chief Chaudhary ended up being a traitor or a rank bad General!! Even during the war, his decisions were naive and foolish. Thank God, that Lt. Gen. Harbaksh Singh did NOT follow the orders of Gen Chaudhary and withdraw in Punjab! More on this asinine Army Chief in the article copied below (because it is so important, and I am not sure how long it will be carried on that web site, so I have put it here).

At 2.30 a.m. the Army Chief, General J.N. Chaudhary, called and spoke to the General and after a heated discussion centered around the major threat that had developed, the Chief ordered the Army Commander to withdraw 11 Corps to hold a line on the Beas river. General Harbakhsh Singh refused to carry out this order. The next morning, 4 Division stabilised the position and when the Chief visited command headquarters at Ambala that afternoon, the 10th, the crisis was over and the subject was not discussed. Had the General carried out these orders, not only would have half of Punjab been under Pakistani occupation but the morale of the Indian Army would have been rock bottom, affecting operations in other theatres as well.

Shastri’s Death

In this article we had discussed what happened during the Tashkent summit – how Ayub Khan added a meaningless phrase “Without resort to arms” – which forced Indian hand into signing the agreement..and how that night the Indian PM died in unusual circumstances.

Lal Bahadur Shastri’s death has remained a mystery! His family suggested that there was a note found in his spectacles case which said “I have been Betrayed”.

RTI plea by Anuj Dhar

Now, a friend, Anuj Dhar – who has written – credibly – about the real story behind Subhash Chandra Bose in his book “Back from Dead” and about the betrayal of India in 1971 by a Cabinet Minister in his book “CIA’s Eye on South Asia”; has turned his attention to the saga of Shastri’s death.[5] So, he filed the RTI with the Indian Government to release the documents relating to Shastri’s death. Government’s response:

the disclosure could harm foreign relations, create disruption in the country and cause breach of parliamentary privilege.

Ok, so we are afraid to even say what happened to our Prime Minister at the HEIGHT of a VERY important war?? Because some foreign power may be offended??

Are we in our right mindsat all??

Interestingly, Anil Shastri, Lal Bahadur Shastri’s son and COngress leader is insisting that the Government come clean with this case. What he says is very incredible and deserves SERIOUS NOTE!!

Being his son, I would like to say there have been doubts lingering in the minds of many people about the mysterious death of Shastriji in Tashkent (the capital of Uzbekistan in the then Soviet Union). I feel the government can dispel suspicions about the cause of his death by declassifying the related information. His death was a very big shock to us and the entire nation. I remember his body had darkish blue spots on the chest, abdomen and back. We had suspected he died under mysterious circumstances.

It has been said that the room in which Shastri was staying while in Tashkent had no phones or bells and if he did have a heart attack, being alone in his room, he may not have been able to call for help. These details themselves point at improper arrangements for him. We are not even mentioning poisoning here and just drawing from the official cause of his death.

Forget about the wrongs done in the war by Army Chief Chaudhary, the wrongs by the then Government in the run up to Lal Bahadur Shastri’s death are just MIND-BOGGLING:

No phone or bells or means of communication in the room of a Head of State, who just signed a CONTROVERSIAL agreement. (So, controversial that his OWN wife refused to talk to him that evening after his signing!!)

No post mortem on the body that had Dark Blue marks all over and when the Head of State died in a foreign country!!??

If the current Prime Minister’s office is silent on such a major National Security breach – of all proportions and ways – one raises questions ABOUT THE honesty of THIS PM itself! What if he goes the same way as Shastri did??

How do we know that we can prevent what happened in Tashkent? But then again, why did we negotiate (unconditionally) on a war that we were ONE WEEK AWAY from having our enemy surrender, UNCONDITIONALLY I may add (as happened in 1971??!!

Reference Links:

1. Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

2. United States Library of Congress Country Studies

3. Silent Guns, Wary Combatants

4. Lt General Harbaksh Singh

5. Shastri’s death to remain a mystery

In 1965 I was deputy secretary (budget and planning) in the Ministry of Defence. It was a Sunday evening in June, shortly after the Rann of Kutch clashes. I was returning from a visit to one of the Sainik Schools — I was the honorary secretary of the Sainik Schools society — when I met M.M. Hooja, then joint director of the Intelligence Bureau (IB), at Delhi’s Palam airport.

I had known Hooja in my earlier post as deputy secretary (joint intelligence organisation) and member of the Joint Intelligence Committee. He offered to drop me home and, in the car, told me IB had intelligence that Pakistan had raised a second armoured division by cheating the Americans. Though the army had been told, it had refused to accept this.

I asked him to communicate this in writing to enable me to bring it to the defence minister’s notice. The next morning I received a top-secret letter from K. Sankaran Nair, deputy-director, IB.

The defence secretary, P.V.R. Rao, was on four months leave. The secretary-in-charge was a new man, A.D. Pandit. I handed over the letter to H.C. Sarin, secretary (defence production), who enjoyed the confidence of the defence minister, Y.B. Chavan. He gave it to the minister for discussion in his daily morning meeting.

When the minister raised the issue, the army chief, General J.N. Chaudhuri argued, according to what Sarin told me, that IB was exaggerating and unable to produce credible evidence. Due to this casual attitude of the army chief, Pakistan was able to spring the surprise of 1st Armoured Division at Khemkaran and 6th Armoured Division at Sialkot.

That the Indian armoured brigade, under Brigadier T.K. Theogaraj, destroyed the Pakistani armoured division reflects to the credit of officers and men of the army, their guts, valour and skills. They had the full support of their corps commander, General J.S. Dhillon, and their army commander, General Harbaksh Singh.

Even for taking a stand at Khemkaran, General Chaudhuri had to be overruled by defence minister Chavan and the prime minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri. the army chief preferred withdrawal to the Beas river. The details may be found in R.D. Pradhan’s bFrom Debacle to Revival. Pradhan was Chavan’s private secretary upto end 1964 and was brought back during the war. Subsequently, he had access to Chavan’s diaries.

Earlier that year, General Chaudhuri had obtained cabinet orders to reduce our medium tank regiments from 11 down to four and increase the light tank regiments from four to 11. He carried this reorganisation through in spite of opposition from professional subordinates.

The Pentagon simulated a ‘game’ in March 1965, according to which Pakistan attacked India on September 1, 1966, and captured Srinagar, with Shastri unable to counter-attack. In reality, Pakistan attacked on September 1, 1965, and Shastri hit back very hard If Pakistanis had not been in such a hurry and had struck a year later with their two divisions of armour, India would have been in real trouble. After the war, General Chaudhuri not only had to abandon his plans for armour reorganisation, but ask the government to hastily import six regiments of medium armour — three T-54 regiments from Czechoslovakia and three T-55 regiments from the USSR.

General Chaudhuri, as was disclosed by Air Chief Marshal P.C. Lal in a later lecture, did not keep the Indian Air Force (IAF) informed of his intending operation in the Lahore sector. The IAF was caught off-guard and incurred avoidable losses of aircraft, including newly-arrived MIG-21s.

The Indian Army was surprised by the Pakistani armour’s sudden appearance through the various aqueducts under the Ichogil canal. This intelligence about the aqueducts was available well in advance, since construction plans of the canal, including the aqueducts, were obtained from the World Bank by IB and provided to the army.

Shekhar Gupta (‘‘1965 in 2005’’, National Interest, June 4, 2005) was not wrong in calling the war one of mutual incompetence. It so happens both Ayub Khan and General Chaudhuri were in the same batch at Sandhurst.

TWO months before the war, in my planning branch, undersecretary I.C. Bansal did elaborate research on the US budgetary documents and calulated American military aid to Pakistan totalled slightly below $ 900 million. When this was put up to the Chiefs of Staff Committee, they (particularly the army chief) rejected the study. In their view, the aid should have been several billions of dollars.

We costed the equipment and facilities and argued it could not be very much more. But it was to no avail. Subsequently it was proved our calculations in the planning branch were not very much off the mark.

So on the one hand General Chaudhuri refused to accept the existence of the second Pakistani armoured division. But at the same time he had an exaggerated view of US aid to Pakistan.

Having negotiated with the Americans on aid for six Indian mountain divisions, we were aware US policy was to provide only six weeks’ war wastage of ammunition at US rates, which were lower than our rates, to aid-receiving countries. On September 2, 1965, through a top-secret telegram, I sought information from S. Guhan, my cadremate and at that time first secretary in our Washington embassy, to check through contacts in the Pentagon what was the ammunition supply rate to Pakistan.

Gohar Ayub Khan’s story of a stolen war plan is probably bogus. But 40 years on, the first full-fledged India-Pakistan war is still a very real presence for many Within a few days Guhan confirmed my assumption and a copy of the top-secret telegram went to General Chaudhuri also. He congratulated me for the information. Indeed, Gohar Ayub Khan has referred to Pakistan suffering from ammunition shortage within a few days of the war beginning.

India had some 90 days war wastage reserves. After the war ended, it was found only eight to 10 per cent of the tank and artillery ammunition had been spent. We had to cancel an order to Yugoslavia for a million rounds of L-70 anti-aircraft ammunition. The order had been placed during the operations.

If the war had been continued for another week, Pakistan would have been forced to surrender. Unfortunately General Chaudhuri advised the prime minister to accept the UN ceasefire proposal since he felt both sides were running out of ammunition. This was far from true for India.

Let me come to some major intelligence failures, even though we were not aware of them at the time. According to an article by Altaf Gauhar — in 1965, the alter ego of President Ayub Khan — in Nation on October 3, 1999, Brigadier Ayub Awan, director of the Pakistani Intelligence Bureau, travelled to Saudi Arabia in early 1965. He contacted Sheikh Abdullah in Jeddah and told him about Operation Gibraltar. Later however, President Ayub decided against taking Sheikh Abdullah’s help.

This version was confirmed by the then CIA operative in Madras (now Chennai), Duane Claridge, who was deputed to meet Sheikh Abdullah and told by him of the coming war. US authorities had, therefore, full knowledge about Operation Gibraltar and Pakistani plans to use American equipment against India as early as March 1965, but chose not to warn India.

This information is available in Claridge’s book A Man for All Seasons. Claridge rose high in the CIA and became deputy director. He was convicted during the Reagan presidency in the Iran-Contra affair, but pardoned.

Pakistan was suffering from an ammunition shortage within days of the war starting. India had 90 days of war wastage reserves. If the war had continued for another week, Pakistan would have been forced to surrender. But India agreed to a UN ceasefire Following all this, the Institute of Defence Analysis (IDA) in the Pentagon simulated a politico-strategic game with Harvard University. According to this game, ‘‘played’’ in March 1965, India lost the war with Pakistan and had to accept US mediation on Kashmir, after losing Srinagar. Though Shastri was advised in the game to counterattack, he was timid and refused.

The verbatim proceedings of this game were published in March 1965 by Doubleday and available in US bookshops. The book was titled Crisis Game, ascribed to author Sidney Giffin.

But our intelligence, civil and military, did not have a clue. In 1967, I picked up a second-hand copy on the pavement outside the London School of Economics. One wonders how much this book influenced President Ayub in initiating Operation Gibraltar.

Strangely enough, in the book Pakistan attacks India on September 1, 1966. In reality it happened on September 1, 1965.

Till today, the valour and skills of the officers and men of that armoured brigade commanded by Brigadier Theogaraj and the roles of Generals Harbaksh and Dhillon in defying General Chaudhuri have not received their due credit.

One American academic — an assistant secretary of state in the Kennedy administration who played a prominent role in preventing India getting combat equipment — ruefully told me that on the eve of the 1965 war he was planning to write a book on ‘the war that changed the fate of the subcontinent’.

Thanks to the valour and tactical skills of those men who confronted the Pakistani Pattons at Asal Uttar, he could never write that book.

The author, a former civil servant, is a defence affairs analyst